A Tale of Two Nephews

I have two nephews.

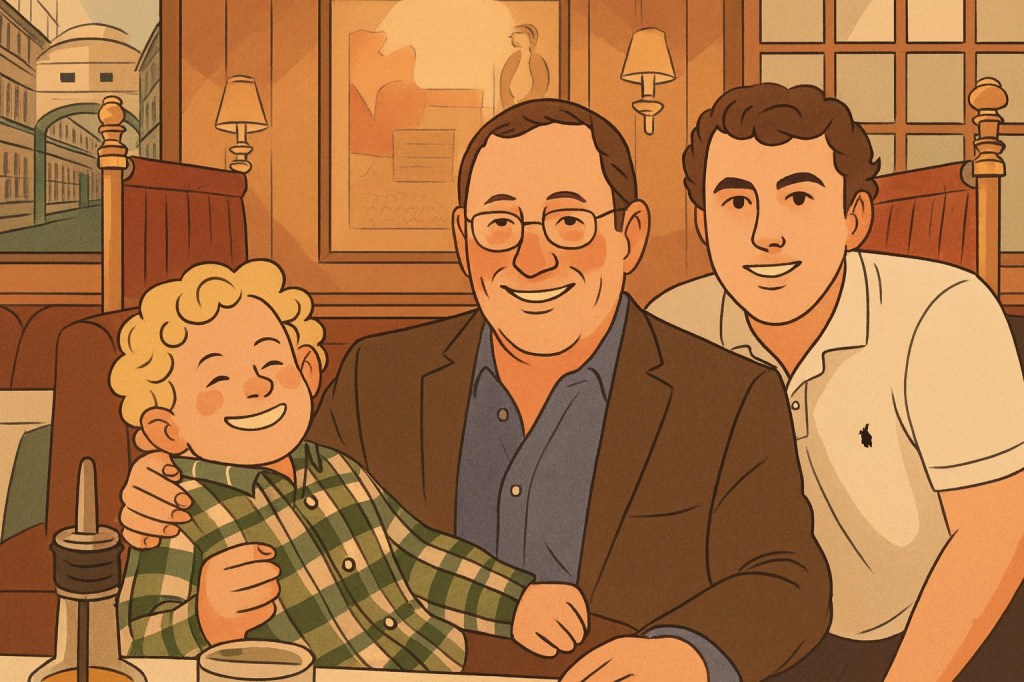

They are much alike. Both stand over six feet tall—handsome by any measure—with light complexions, rosy cheeks, dimples as deep as divots, and unruly mops of blond hair. They are athletic: one a former rower and lifelong gym rat, the other a onetime baseball player and current Peloton warrior. Both are intelligent, blessed with prodigious memories, and keenly aware that being smart is not an end in itself. They wear it lightly, never flaunting it except when necessary. And they share an excellent sense of humor—at least if laughing at their uncle’s dad jokes is the standard.

The older of the two, Sean, a finance director at one of the nation’s leading financial firms, is not technically my nephew. He is the son of my best friend, but we have been bonded since infancy. In fact, when I visited his home when he was a child, he was far more likely to hang out with his funcle than his dad. This was probably more a function of bribery than love. I bought him his first hot-fudge sundae, took him to restaurants where he could eat prodigious amounts of steak, and once treated him to a day at Yankee Stadium—seats on the rail behind home plate. After demolishing an enormous slice of chocolate cake at Ruby Foo’s, he declared it “the best day ever.”

Both his father and brother passed away during the COVID pandemic, which tightened our bond—already strong—like a pair of jeans after the holidays. We don’t talk every day, and sometimes not for weeks, but when we do the conversations are long, good-natured, and often substantive.

My other nephew, Oliver, is a sophomore at NYU. When I look at him, I see my father. The similarities in demeanor and appearance are striking. Like my dad, Oliver never takes things at face value. He wants to be sure the white sheep aren’t black on the other side. I love talking to him. He soaks up our family history like Wi-Fi in a coffee shop, and I always know he’s going to have a unique take on current events and politics.

They have met only once, at our wedding. Sean was a college student at the time, and Oliver was five. For reasons unknown, they bonded instantly, with Oliver literally wrapping himself around Sean’s leg as Sean tried to navigate the party. It was adorable.

As much as they have in common, they see the world through very different lenses.

This really hit home last week during an email exchange I had with Sean. Months earlier, Sean and I had made a bet about the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. I argued they were ill-advised and would cause long-term economic harm. Sean believed they would ultimately level the playing field and that fair trade—not free trade—would prevail. Rather than argue endlessly, we agreed on a wager: whoever was right would buy the other a steak dinner with all the trimmings.

I decided I had won and sent him the following email:

Hi Seany.

And because I’m feeling feisty this morning—it’s 11 degrees—here’s my question of the day: Is it socialism to give farmers a $16B care package to make up for losses caused by tariffs?

Follow-up question: How long do we keep these subsidies going, considering farmers’ distribution channels have been irrevocably broken?

And have I won the bet yet?

He wrote back:

Hmmm. Don’t know enough about that. In general, farming is important for national security, but I haven’t read enough about why the subsidies do—or don’t—exist.

I do have an overarching thought on the continued push toward socialism. I think it’s because we have a generation of people who feel left out. Why are we not trying to fix the underlying issues with more housing, better education, and an improved healthcare system? Instead, we’re trying to tax our way out of it, which won’t work. You have to fix the root cause and improve spending efficiency.

A finance guy’s answer, without doubt. Also, in my opinion, completely wrong.

I responded:

First, I hope you know I was just feeling mischievous and thought no one teases Sean nearly enough.

Second, the argument that farming is subsidized because it’s important to national security—and therefore this isn’t socialism—is specious in this case. The reason farmers’ markets fell apart was:

- tariffs, and

- a lack of farmhands due to immigration shutdowns.

In other words, Trump caused the problem and now wants to subsidize his own screw-up so he doesn’t lose his base. It’s a bit like the arsonist running the fire department.

Finally, the idea that we’re trying to tax our way out of systemic problems like housing is also specious. It’s a talking point, not reality. Our relative tax rate is in the lower half of the G20. Socialism is gaining popularity because of the income gap.

In 1980, the U.S. still had what economists called a large middle class. The top 10% earned about 34% of national income, while the bottom 50% received around 20%. CEO pay averaged 30–40× the typical worker, and upward mobility still existed for many families.

By 2024, the picture is radically different. The top 10% now control roughly 48–50% of all income, while the bottom 50% receive about 13%. The top 1% alone holds roughly 32–35% of total national wealth. CEO pay has ballooned to 300–400× the average worker. In real terms, wages have barely moved, while wealth at the top has exploded.

And you have to admit—I won the bet. 😊

He chose not to reply.

But it got me thinking: how would my nephew Oliver respond?

One thing I haven’t mentioned yet is that Oliver is a self-described communist who, on a recent trip to London, made a pilgrimage to the places where Marx and Engels lived and worked while in exile. Since he’s buried in final exams, I didn’t ask him directly. Instead, I asked myself how an avowed communist might respond:

Uncle Paul, the $16B farmer bailout isn’t socialism at all. It’s a familiar feature of capitalism: privatized profit, socialized loss. Socialism isn’t when the state cleans up damage caused by market shocks or policy mistakes—it’s when production itself is collectively owned and democratically run. Writing checks to farmers after tariffs hurt them doesn’t change who owns the land, who controls distribution, or who captures long-term value. It just stabilizes the system.

To which I would reply:

I hear you. But no communist state that consolidated power has sustained genuinely free elections or broad free speech. There were moments of openness, but once the party became the state, dissent was curtailed. Opposition was framed as counter-revolutionary, and free speech became a threat rather than a safeguard.

And isn’t that exactly what happens with unfettered capitalism? A few at the top accumulate all the power and money while everyone else fights for crumbs. Communism as a theory is magnificent, but in practice it has proven no better than capitalism without guardrails.

Here’s the sad part—the part where I sound like the old guy.

Both of my nephews have wonderful intentions. Both want a better world than the one they inherited. They’re just approaching it from wildly different starting points. That may be the hallmark of our time.

So I would say this:

To Sean: The last time we saw this level of income and wealth disparity was at the end of the Gilded Age. It led to rebellion, unrest, and the rise of unions. We need to put guardrails back on capitalism quickly—or what follows will be ugly and may destroy our democracy.

To Oliver: If communism were practiced in its purest form, it might be wonderful. But it never works that way. Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. When people lose power to the state, it almost always ends in revolution and destruction.

No doubt—because both of them are wisenheimers, they’d ask:

“So, old man, what’s your solution?”

To which, being the Dickens I am, would simply offer them this:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Because sometimes the truest answer isn’t a policy or an ideology, but the uncomfortable recognition that we are once again living inside a moment history knows all too well.