Baby, It’s Hot Outside

How hot? The cisterns that hold our water are located in the eaves of our attic, providing additional water pressure for the home. In the three weeks we have been here, we have never had to turn on our hot water heater to shower. The water that comes out of the tap is warm enough on its own.

There is no doubt in the minds of most Cariocas (Rio de Janeirians) that this is due to global climate change. I would argue that they probably understand it better than most.

All they need to do is look southwest to the Pantanal, the largest tropical wetland and flooded grassland in the world. It provides essential sanctuaries for migratory birds, critical nursery grounds for aquatic life, and refuges for creatures such as the yacare caiman and deer. But it is under threat. Climate change has dropped water levels to nearly half of what they were 20 years ago. Commercial exploitation—through fishing, cattle ranching, pollution, and deforestation—has contributed to the destruction of what was once one of the world’s most pristine ecosystems.

And then, there is the Amazon. The lungs of the world have emphysema. Over the last twenty years, more than 186,000 square kilometers of the Amazon have been deforested. To put that in perspective, that is larger than two-thirds of the countries in the UN—or imagine the entire state of Oregon stripped of trees in a single generation. The Amazon helps absorb the world’s CO₂ emissions. Less forest means more CO₂, which means higher temperatures worldwide. It affects regional and global rainfall patterns, decreases biodiversity, hinders medical research, and leads to the destruction of indigenous peoples’ habitats.

But honestly, Cariocas don’t need to look beyond their own city to understand climate change. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the jungle in the hills of Rio was systematically harvested for building materials, firewood, coffee plantations, and livestock grazing. The streams that fed the forest were a major source of water for the city, but without the forest, there was nothing to hold the streams back. When it rained, there were flash floods and landslides. When there was no rain, there was no water, and the tropical city went thirsty.

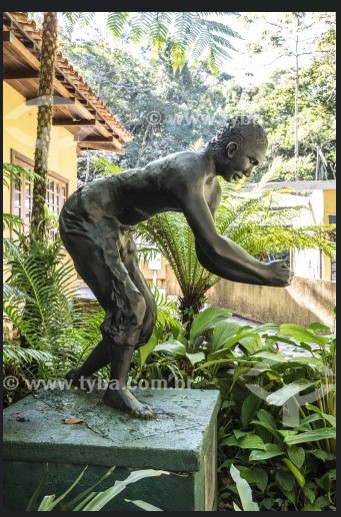

In 1861, recognizing the problem, Emperor Pedro II placed the land under federal control and initiated efforts to restore the forest over the now-barren slopes and abandoned fields. The replanting was carried out by six enslaved people—Elueuteiro, Constantino, Manuel, Mateus, and Maria. Over the next 16 years, they planted over 100,000 trees. Today, the Tijuca National Forest, covering nearly 4,000 hectares, is the largest urban forest in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

As I walk around our neighborhood in the near-100-degree heat, looking at the forest that surrounds us, I can’t help but think about the lessons we should have learned.

Left unconstrained, individuals and corporations will exploit and destroy the environment to enrich themselves, with no regard for the consequences. It is an immutable law—no industry has ever self-regulated in favor of the greater public good. As Teddy Roosevelt (back when Republicans were the progressives) once said:

“Defenders of the short-sighted men who, in their greed and selfishness, will, if permitted, rob our country of half its charm by their reckless extermination of all useful and beautiful wild things, sometimes seek to champion them by saying the ‘game belongs to the people.’ So it does; and not merely to the people now alive, but to the unborn people.”

Teddy believed, as did Pedro II, as do I, that government must play an active role in protecting the environment—not just for us, but for the generations to come. This includes supporting global agreements such as the Paris Climate Accords and the Rio Earth Summit. It means investing in clean energy initiatives like solar, wind, and nuclear power and setting environmental goals for emission standards in transportation and industry.

What it certainly does not mean is denial.

I cannot deny walking around our neighborhood in the early afternoon, in 100-degree heat, downing a liter and a half of water. And the government should not be denying climate change, as the Trump administration has done—by denying farmers access to climate data, withdrawing from the Paris Accords, rolling back renewable energy support, slashing budgets for climate research, and reducing environmental protections.

Many years ago, I was walking through a forest in the Tel Dan Nature Reserve in Northern Israel with my father and a guide. It is a beautiful place, full of streams and springs, one of the major sources of the River Jordan. At one point, we came across a little boy—no more than seven or eight years old—who was joyfully peeing into one of the streams. Our guide said to him,

“Don’t you know that if you piss in the water, it will come out of your tap in Tel Aviv?”

Without missing a beat, the boy replied,

“That’s okay. I live in Jerusalem.”

Beyond being a wonderful story about the inbred chutzpah of Israelis, it is also a powerful metaphor. Children do not understand the consequences of their actions. It is up to adults to teach them that when you piss in a shared resource, you foul it for everyone.

The Trump administration needs to understand that denying climate change, silencing discussions about it, or refusing to participate in global solutions does not alter reality. All it means is that we continue to piss into the springs we all drink from