Brazil’s history with slavery is shameful.

Brazil imported more than 4.8 million Africans as slaves—almost eleven times more than the American colonies and the U.S. during its own shameful past. Even more shocking is that 50% of those who arrived in bondage in Brazil died within five years of their arrival. That is mass murder, a holocaust by any definition.

I first learned of Brazil’s ugly past with slavery on my first date with my wife.

We had met the night before when we became dinner companions on the cruise ship where we were both traveling. She was radiant, beautiful, and had a delightful Brazilian accent. How could I say no when, after finding out that I had never been to Salvador, she volunteered to be my tour guide?

If you don’t know Salvador (saw-va-DOH), it was the colonial capital of Brazil and the heart of its slave trade. When you arrive in the upper city and the neighborhood of Pelourinho (it means whipping post in Portuguese) , it looks like a movie set depicting the Brazilian colonial era. The Baroque and Rococo architecture features pastel-colored buildings adorned with decorative tiles, ornate balconies, and grand wooden doors. You are greeted by Black women wearing Traje de Baiana (Bahiana attire)—long, flowing, multi-layered, petticoated dresses with intricately patterned lace blouses, shawls, and head wraps made of patterned fabrics. Their beaded necklaces provide percussion as they move to a beat only they can hear.

I am enchanted.

As we make our way to the Igreja de São Francisco (The Church of Saint Francis), we come across a group of people watching a troop of shirtless teenagers in white baggy pants demonstrating Capoeira. I had heard of this mix of martial arts, dance, and music before but had never seen it performed live. Elaine tells me that this is uniquely Brazilian, created by the enslaved Africans brought to Brazil as a means of self-defense. Their movements are mesmerizing, and we watch and applaud as they demonstrate their skills.

Just before we reach the church, we stop before a statue of a shirtless Black man standing on one foot, holding a large spear, gazing into the distance. His face is proud and defiant. Elaine tells me this is Zumbi dos Palmares, King of the Slaves. An escaped slave, he was the leader of the largest quilombo—a settlement of escaped slaves—in northern Brazil. He fiercely fought the Portuguese and their efforts to subjugate the quilombo until his death in 1695. He is celebrated for his resistance and remembered every year on November 20, Dia da Consciência Negra (Black Consciousness Day).

I am dumbfounded. Not because there is a statue honoring this man, but because I know that the history of enslavement in the U.S. is largely glossed over in most school curriculums. There are still those who believe slavery was relatively benign and that those who were enslaved actually benefited from their enslavement.

I need to make an admission here. I do not care much for churches. As a Jew, they make me feel uncomfortable and a bit paranoid. I wonder whether I will be found out by the parishioners and tossed out on my ear for being a heathen, or whether a bolt of lightning will come from the heavens for failing to accept Jesus as my savior. That said, the Igreja de São Francisco is amazing. From the decorative tiles in its courtyard to its gold-leaf interior with elaborate wood carvings, you can sense that those who built the church were celebrating their God with all the skills they possessed.

As we leave the church, we are confronted by a beggar. He is in a wheelchair, and his legs and arms appear to have been put on backwards. It is disturbing—horrifying, really. It is a punch-in-the-nose reminder of the abject poverty some suffer here, and I cannot get a 20-real note out of my pocket fast enough.

We eventually make our way to the Mercado Modelo and find a table at an outside café, ordering some of the coldest beer I have ever had. It goes down way too easily, so I have another, and Elaine orders us some pastéis de camarão, the Brazilian version of empanadas. As we eat and drink, we are entertained by a series of performers, including samba dancers, Axé, and samba-reggae musicians. When I mention to Elaine how much I enjoy the entertainment, she tells me that the Afro-Brazilian heritage in music and dance is one of the reasons Michael Jackson came to Salvador to film the music video for “They Don’t Care About Us.”

I know the song. It is an anthem about racism:

All I want to say is that they don’t really care about us

Don’t worry what people say, we know the truth

All I want to say is that they don’t really care about us

Enough is enough of this garbage

All I want to say is that they don’t really care about us

Skinhead, deadhead Everybody gone bad

Situation aggravation Everybody, allegation

In the suite on the news Everybody, dog food

Bang-bang, shock dead Everybody’s gone mad

I ask, “Why do you think he came here to film the video?”

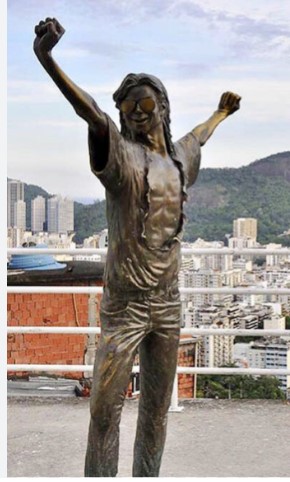

She tells me she believes he came here for three reasons: first, because of the rich musical tradition of this place and the beat he was trying to create, and second, because of the racism that still exists in Brazil and finally because the only country in the world with a more shameful history of enslavement than the US is Brazil. She explains that even though over fifty percent of the Brazilian population identifies as Black or “pardo” (mixed race), racial prejudice is very much alive in Brazil. She tells me that Michael is a legend in the favelas, there is even a statue of him in Dona Marta favella, because he came here to shine a light on the prejudice and poverty they suffer through every day.

I think about that day a lot these days, especially since Trump and his supporters have launched a war on DEI. Brazil, a country where more than half of the population is at least partially of African heritage, recognizes that it has a race problem. They have enacted specific policies such as:

- Law 14,553/2023, amending the Brazilian Statute of Racial Equality, which mandates that employers include fields for employees to self-identify their racial or ethnic backgrounds in administrative documents.

- Affirmative action policies such as income- and race-based quotas in federal universities since 2012, improving access to higher education for underrepresented groups and leading to enhanced labor market prospects.

- The Ministry of Racial Equality, reestablished in 2023, is dedicated to promoting racial equality and combating discrimination.

You cannot fix a problem until you acknowledge you have one. And you have to be blind not to see the racial problem we have in the U.S. Brazil still has a long way to go but at least they understand they have a problem.

This is a long way to say:

- Diversity is not a swear word. It means giving ourselves the opportunity to see the world from multiple perspectives. Perspective is the key to seeing the whole picture, not just a single frame.

- Equity means providing people with a level playing field. Fair play is at the center of our culture. When there is inequity, fair play does not exist, and we fail as a society.

- Inclusion means feeling as if you belong. Many of us have felt like outsiders looking in at one time or another. It is a lonely feeling. Making someone feel welcome is an obligation we have as a society. Understanding how some may not feel included is called kindness, and it is not a sin.